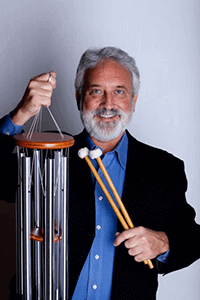

PAS Hall of Fame:

Garry Kvistad

(b. November 9, 1949 )

by Lauren Vogel Weiss

During this time of a global pandemic, racial unrest, and economic uncertainty, there is a peaceful serenity from the soothing sounds (the natural harmonic overtone series) of the “Healing Chime,” made by Woodstock Percussion. The man behind those musical chimes is Garry Kvistad, not only a master tuner and instrument builder, but a longtime performing percussionist and champion of the arts.

“I’ve known from a young age that good sounds are healing,” he explains, “and I’ve made the study of music and sounds my life’s work.”

In addition to founding Woodstock Chimes, Kvistad—a self-described “old hippie” who has spent the past four decades in New York’s Hudson Valley—has been a member of three historic ensembles: the Blackearth Percussion Group, Steve Reich and Musicians, and Nexus.

“It’s always been a mission of mine to promote percussion,” Kvistad states. “Even though we’ve been in the back of the orchestra, I wanted to turn people on to the enormous variety of percussion. There’s more to percussion than an occasional cymbal crash or playing a backbeat in a rock song.”

Born on November 9, 1949 in Oak Park, Illinois, Garry Kvistad was raised in nearby Franklin Park, where his father, a former trumpet player, served as mayor. “Our parents loved swing, classical, and jazz,” remembers Garry, “and were very inspirational when it came to music.” In fourth grade band, he chose percussion. “I was originally attracted to keyboard percussion,” Garry recalls, “but then developed a love of timpani when I started listening to orchestral recordings.” Because his older brother Rick was studying with Cloyd Duff at Oberlin, Garry was drawn to recordings of the Cleveland Orchestra with Duff playing timpani. “It was mind-blowing,” he describes. “Not only the music, but to hear a Beethoven symphony for the first time and have it really affect you. Plus, focusing on the timpani and the beauty of [Duff’s] musicianship was amazing.”

One of Garry’s first teachers was orchestral percussionist Al Payson. “He was an incredible teacher,” Kvistad says. “We would play snare drum on a rubber pad in his basement, and also work on timpani, with an emphasis on tuning. It was wonderful to study with someone who had orchestral experience. And I would see him play when my parents took us to the Chicago Symphony.”

In 1963 and ’64, Garry attended summer music camp in Interlochen, Michigan. “That’s where I began to study with Jack McKenzie, who was teaching at the University of Illinois. He was very influential in my appreciation of chamber music and percussion ensemble.”

After his freshman year of high school, Garry was “recruited” to attend the recently opened Interlochen Arts Academy. “Jack McKenzie would fly up from Champaign-Urbana once a month to teach, along with his grad assistant Michael Ranta. They turned us on to Harry Partch, Lou Harrison, and John Cage.”

During his senior year at Interlochen, Garry won the concerto competition with a performance of Darius Milhaud’s “Concerto for Percussion and Small Orchestra,” becoming the first percussionist in the school’s history to win.

Upon graduating from Interlochen in 1967, Kvistad decided to attend Oberlin College so he could study with Cloyd Duff. “It was all about sound and musicianship,” Garry says. “[Duff’s] mallets defined his sound, but it was also his approach. He didn’t focus on outrageous technique but did exactly what he needed to do to get this amazing sound out of the timpani that added a really special voice to the orchestra.”

When Duff stopped teaching at Oberlin after Garry’s first year, Rich Weiner, newly appointed Principal Percussionist of the Cleveland Orchestra, replaced him. “It was a stroke of luck for me because I wanted to study more keyboard percussion, and Weiner was an incredible mallet player. He emphasized ensemble playing and sound.”

In the summer of 1968, Garry was selected as a fellow to attend the prestigious Tanglewood Music Festival in Massachusetts. “I was the youngest person in the program,” he remembers. “I was there with people like Paul Berns, Peter Magadini, and Michael Tilson Thomas. Our conductors included Aaron Copland and Gunther Schuller. I also played timpani in Bartok’s ‘Concerto for Orchestra,’ under the direction of Erich Leinsdorf, for a live PBS broadcast; that was intense.”

The following summer, Kvistad joined Chicago’s Grant Park Orchestra, where he played percussion and timpani for the next five summers. “We went through a lot of repertoire with two concerts each week,” he explains. “I even had a chance to meet Max Roach when he played Peter Phillips’ ‘Concerto for Jazz Drums, Percussion Ensemble, and Orchestra.’”

Back at Oberlin, Kvistad was involved in the Contemporary Music Ensemble as well as the orchestra. “I realized that we could apply orchestral percussion techniques to modern music. You weren’t picking up just any tin can; you wanted to create this exact sound. So we applied traditional percussion methods to Cage’s ‘Third Construction,’ even though we were playing conch shells, pod rattles, and Chinese tom-toms.”

During his senior year at Oberlin, Garry played “The King of Denmark” by Morton Feldman, and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Zyklus” and “Kontakte.” “Based on his amazing senior recital of insanely difficult works, Garry was asked to perform on the senior honors recital,” remembers Rick Kvistad. “All the other performers played very challenging and showy pieces on violin and piano, while Garry brought the house down with John Cage’s ‘4´33´´’ on a marimba!”

Following his graduation from Oberlin in 1971 with a Bachelor of Music degree, Garry applied to the University of Illinois. “I had taken some lessons from Tom Siwe because he was involved with the music of Stockhausen and Cage,” Kvistad explains. “A few weeks before I was to start grad school, Siwe told me there was an opening in Lukas Foss’s group, the Creative Associates, and he wanted to recommend me! So I went to Buffalo, New York. I was able to sub with the Buffalo Philharmonic and play some musicals in town as a jobber. And that’s where I met Jan Williams.”

PERCUSSION ENSEMBLES

Blackearth Percussion Group

Jan Williams was the percussion instructor at SUNY-Buffalo, as well as a member of the recently defunct New Percussion Quartet. “One day I was in his studio and saw a pile of music,” Kvistad recalls. “He told me it was entries from their composition contest. There were 150 pieces for percussion quartet that had not yet been performed! I asked if I could play some of the pieces, and Jan gave me the whole pile! That’s when I got the idea to form my own ensemble.”

Kvistad contacted Allen Otte, a classmate from Oberlin; Michael Udow, who he knew from Interlochen; and his brother Rick, then principal percussionist with the Pittsburgh Symphony. “Our parents had a farm near Madison, Wisconsin,” Garry explains. “The dream was to rehearse in the barn, live in the farmhouse, and grow our own food, like a band of hippies. We had no idea how hard that would be—or how cold it would be in an uninsulated barn! We were going to name our group the Blanchardville Percussion Quartet, after the nearest town. But my father said there were other towns with better names, so we became the Blackearth Percussion Group.” Soon after the quartet was formed, Udow received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in Poland, so he was temporarily replaced by Chris Braun, another classmate from Oberlin.

Tom Siwe invited the fledgling ensemble to be in residence at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana, where they spent the fall of 1972. By the spring semester, Al O’Connor invited them to Northern Illinois University in DeKalb as artists-in-residence, as well as associate professors of music. This made Blackearth America’s first full-time professional percussion ensemble, and they remained in residence at NIU for five years.

“I had always been interested in the music of Harrison, Cage, and Partch, who used found instruments, and even music sculptures. Using that inspiration, I wanted to learn how to make instruments, so I signed up for woodworking and metallurgy courses. I also studied with Thomas Rossing, one of the physics professors who specialized in the acoustics of percussion instruments. We did a lot of experiments in the lab, and years later I had the honor of writing the foreword for his book, Acoustics of Percussion Instruments.”

Over the next several years, Black-earth Percussion Group played over 150 concerts in the U.S., Canada, and Europe, including 38 world premieres. One of their signature pieces was Cage’s “Third Construction.” “It was an incredible piece to apply our traditional performance techniques to,” Kvistad explains. “We spent an entire month rehearsing and then played it on tour for two years. The audiences in Europe flipped out over it, but the performance that stands out for me was at Pennsylvania State University in 1977 for the Acoustical Society of America’s conference; performing for acousticians and musicians alike was pretty special.”

“We played a wide variety of avant-garde music, including some with elements of theater,” Rick Kvistad remembers. “Garry—who in high school was a trampoline star as well as a percussion virtuoso—stole the show, putting his gymnastic skills on display by walking on his hands during the improvised sections!”

One of Garry’s favorite recordings (of the three dozen-plus he has played on) is The Blackearth Percussion Group (Opus One, No. 22). “It was very special,” he recalls. “We did a piece for 20 suspended cymbals [‘Tune’ by Bertoncini], ‘Take That’ [by William Albright], and Cage’s ‘Amores.’”

The group saw several personnel changes over the years; [the late] James Baird and David Johnson became members when Udow and Rick Kvistad left. “The members of every successful chamber music group will tell you the same thing,” states Allen Otte. “There are certain principles on which everyone has to be on the same page; then there are other aspects where someone clearly has to rise to being a leader. Garry always had the most courage and vision about adventuresome next steps in building a career and a life in the kind of music we loved, and he has continued to prove this excellent ‘business sense’ throughout his life. What resonates most for me is that this was always done with a positive and good-natured attitude.”

By the time Blackearth left NIU in 1977, Garry had earned his Master of Music degree in performance. The ensemble—now a trio comprised of Kvistad, Otte, and Stacey Bowers—spent its last two years at the University of Cincinnati-Conservatory of Music. When Bowers decided to leave in 1979, Garry decided it was time to move on.

Kvistad and his wife, Diane, traveled around the northeastern U.S. and fell in love with Woodstock, New York. “The environment is unbelievable and the connection to the arts is fantastic!” he explains. “There were tons of musicians in the area, and it was only two hours from New York City.” They moved there on July 4, 1979.

Steve Reich and Musicians

“At PASIC ’79, I met James Preiss, who was teaching at the Manhattan School of Music and playing with Steve Reich and Musicians,” Kvistad remembers. “When David Van Tieghem left the ensemble, Steve asked Jim if he knew any percussionists, and Jim told him I had recently moved to New York. My brother, Rick, played ‘Clapping Music’ with Steve the year before in California, so he knew the name. Steve called and asked if I would like to play a gig with them at The Bottom Line in The Village. So there I was, playing ‘Xylophone 2’ next to Bob Becker! That’s where I met Russell Hartenberger, too. The next piece Steve wrote was ‘Tehillim,’ and that’s when he asked me to join the group.” Kvistad has played with the ensemble for the past four decades, including on their 1998 Grammy-winning recording Reich: Music for 18 Musicians (ECM), another of Garry’s favorite albums.

‘When I first heard a recording of ‘Drumming’ in the ’70s, it was mind-blowing!” Garry says. “That’s what turned me on to Steve Reich. And anytime we played ‘Music for 18 Musicians’ was memorable. Everything I did with Steve was very special, and it changed my life.”

“Garry Kvistad has performed with us in major venues around the world,” states Reich. “He was also our social director, always knowing the best places to eat and drink after the concert. Garry is a really first-rate percussionist and a wonderful human being.”

Nexus

In 2002, John Wyre resigned from Nexus, leaving an opening in the world-renowned percussion quintet. “Bob [Becker] and I performed with Garry in the Reich ensemble,” remembers Russell Hartenberger, “and Bill [Cahn] joined us from time to time, so we all knew Garry and his wonderful musicianship well. Consequently, it was an easy decision to bring Garry into Nexus when John retired. In addition to being a great percussionist, Garry knew all our in-jokes and contributed many new ones, so his transition into Nexus was a smooth one.”

One of Kvistad’s first performances with Nexus was at PASIC 2002 in Columbus, Ohio, where they performed Reich’s “Music for Pieces of Wood” and “Drumming.” “It’s always great to play for other professionals or young percussionists,” Kvistad says. “Rich Weiner once told me that if you join a group, you don’t want to be the best player, because you want to be challenged. So Nexus was perfect for me. Those guys are so amazing to play with; it’s a special creative energy that sweeps you away.”

“I first heard Garry’s playing in 1976 when I found a bootleg tape of Cage’s ‘Third Construction’ performed by the Blackearth Percussion Group,” recalls Bob Becker. “I will always remember hearing the wonderful performance of the piece for the first time. Although Garry didn’t join Nexus until 2002, I felt like he had already become a member in 1990 when he designed and fabricated the fabulous sets of chimes for Toru Takemitsu’s concerto ‘From me flows what you call Time.’”

Since Kvistad joined Nexus, they have performed that concerto almost a dozen times with orchestras across the globe. They have premiered numerous other pieces, including Ellen Taafe Zwilich’s “Rituals” and Eric Ewazen’s “The Eternal Dance of Life” (at PASIC 2008 in Austin, Texas), and recorded ten albums since 2002.

WOODSTOCK PERCUSSION

Running parallel to Kvisted’s performing career is a successful business venture, Woodstock Percussion, Inc., which has thrived over the past four decades. “I always thought I would make windchimes because I wanted to hear the tunings of the ancient scales that Harry Partch wrote about,” says Kvistad. “By the time we moved to Woodstock in 1979, I was making woodblocks and log drums, and tuning xylophones, marimbas, glockenspiels, and vibraphones for other percussionists—and I had already made three windchimes tuned to Partch’s Chimes of Olympos.

“I read Partch’s Genesis of a Music,” Kvistad continues. “I was intrigued by the fact that ancient musicians wrote music that we had no idea what it sounded like, but we knew the scales that they used, even though they were not frequencies found on the modern piano. I realized there were literally thousands of different tuning systems throughout the world and throughout the ages. One of them was Olympos, a Greek flute player from the 7th century B.C. His scale was a pentatonic scale, but it had two half steps in it—a minor third and a minor sixth—and I thought that was really cool. Because Partch had a G tuning fork, that is the only note of his music that lands on an equal-tempered scale. So this was a minor pentatonic scale—G, A, B-flat, D, E-flat, and then the octave. I used tubes from lawn chairs I had found in the dump to make a little metallophone tuned to those specific frequencies and thought they sounded beautiful together. But how could I share this with other people? Windchimes—they’re perfect! Back then, windchimes were made by visual artists and looked cool, but most of them didn’t sound very good. I drilled the holes at the nodal points, the clapper hit close to the center, which had the largest sound, and the windcatchers were the right shape and weight to activate it. The one thing I brought to that world was an improvement of sound.”

One of the first marketing promotions for his fledgling business was a small exhibit booth at PASIC ’79 in New York City. “We realized that the wholesale market would be better for us than a retail one,” Kvisted says. “Diane had inherent business skills, and she took over sales. Marketing was more interesting to me.” Their daughter Maya is a graphic artist and does all the catalogs for the company. The business also distributes a line of award-winning musical instruments and toys called the Woodstock Music Collection, as well as soothing home and garden decor. They continue to design gifts and accessories, resulting in over 400 products. Woodstock also donated a 12-foot chime to Rhythm! Discovery Center in Indianapolis.

Garry and Diane Kvistad started the Woodstock Chimes Foundation in 1986. “We realized how tough it was for artists to get established, and we wanted to help out, especially in our community,” he explains. “But we also wanted to help out in humanitarian areas. For two decades, I was Chairman of the Byrdcliffe Guild, the oldest utopian arts colony in America, and Diane joined the Board of Directors for the Maverick Concert Hall [where Cage’s ‘4´33´´’ was premiered in 1952] and the Family of Woodstock, which provided people with food, housing, and counseling. We helped to develop an ethnomusicology department at Bard College by loaning an entire gamelan orchestra to them, which is still going strong 20 years later. We also commissioned a couple of pieces by Peter Schickele that Nexus has premiered and recorded. We’ve managed to give away close to three million dollars over the years.”

The Woodstock Chimes Foundation has also supported two concert series in the Hudson Valley: Woodstock Beat and the Drum Boogie Festival. The Foundation paid the musicians and production expenses, and all the proceeds went to the organizations.

Woodstock Beat began in 1991 as a musical fundraiser for the Woodstock Guild. Performers over the years included Nexus, Peter Schickele and his P.D.Q. Bach ensemble; Paul Winter; a trio with local residents Jack DeJohnette, Pat Metheny, and John Patitucci; and a full production of Igor Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat for the 100th anniversary of the Guild’s Byrdcliffe Arts Colony in 2003. The concert series wound down in 2009 as Kvistad’s attention turned to other endeavors.

The biennial Drum Boogie Festival, a free, family-oriented multi-cultural event featuring drumming, dance, and voice, began in 2009. Kvistad serves as producer, performer, and master of ceremonies for the popular event. Performances have included a tribute to xylophone ragtime virtuoso George Hamilton Green, a former resident of Woodstock who is buried in the city’s Artists Cemetery; African and rudimental drumming performed by Nexus; progressive jazz featuring Jack DeJohnette, who has performed at each festival; Indian drumming; gamelan; steel pans; and more. The 2019 edition saw a performance of Reich’s “Drumming” by Nexus and So Percussion.

In addition to performing, Kvistad teaches clinics, including “Sound Science.” “I wanted to share what I had learned from studying acoustics with Dr. Rossing,” explains Garry, “and show percussionists how the technical approach to an instrument would create different sounds, as well as different mallets, and even different instruments. When a composer calls for a gong, there are thousands of different sizes, sounds, and pitches to choose from. That’s one thing I’ve always loved about percussion—the variety.”

Kvistad also gave a TedX talk at Monmouth College in New Jersey in 2016. Titled “Good Vibrations: A Life of Harmony,” he described his love of sounds as well as his fascination with ancient musical scales and how he learned to build and tune instruments. (A preview of his talk can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tzS0hCWvJ7c).

In addition to his PAS Hall of Fame honor, Garry received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Northern Illinois University (2011), the inaugural ICON Honors Achievement Award from the Atlanta Gift Mart (2010), Ernst & Young/Inc. Magazine’s Entrepreneur of the Year Award for Southern New England (1995), and was a state delegate to the White House Conference on Small Business (1995).

“Garry is the only person I know who can run an international manufacturing and distribution company like Woodstock Chimes in the morning, and perform worldwide in the evening at the highest level with ensembles like Nexus and Steve Reich and Musicians,” states Bill Cahn. “On top of that, he uses his considerable people skills to bring great musicians together to produce his Drum Boogie Festivals and to support his community through his foundation work. The icing on the cake for Nexus is that Garry makes a knock-out margarita!”

“After nearly forty years playing together in two major touring groups,” says Bob Becker, “I’m still learning from him—and I don’t mean only the new jokes!”

How would Garry liked to be remembered? “As someone who brought joy and peace to people,” he humbly replies, “either through performances I was involved with or the millions of windchimes that are all over the world, telling a musical story. They bring joy to a lot of people, and that’s going to last longer than anybody remembering me.”

Garry Kvistad is a performer, businessman, instrument builder, educator, author, and philanthropist, but, he says, “I’m a person with a passion for music and sound.”